Written by: Fares Al-Dhahabi

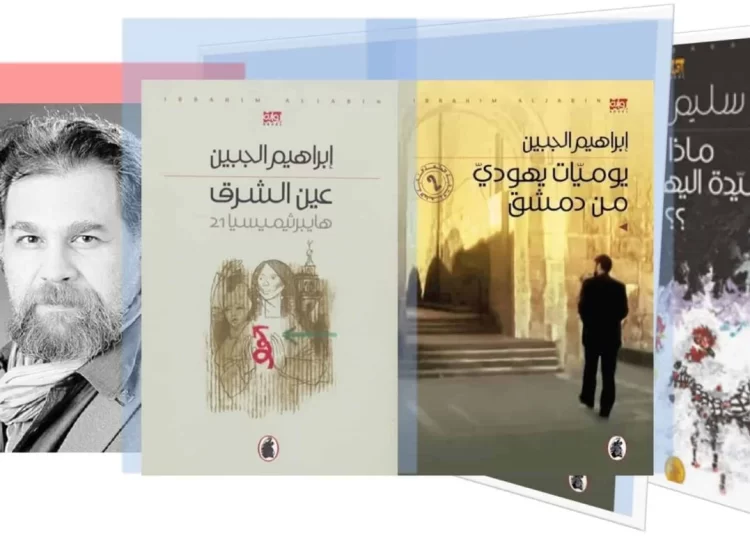

In 2007, the distinguished poet and journalist Ibrahim Al-Jabin published his first novel, Diaries of a Jew in Damascus, which caused a shock similar to throwing a stone into still waters. The reactions to the novel were mixed, some positive, some negative, because it dared to address one of the taboos in Syrian and Arab literature in general: the portrayal of the Arab Jew and the rehumanization of the Jewish figure in the Arab consciousness. For a long time, artistic representations of one of the essential components of Arab societies were stereotyped. Al-Jabin simply shattered this deteriorating taboo, opening the conversation about the Jews of Qamishli, their relationship with the Kurds, and then the relationship between the Damascenes and the Jews and their deep-rooted presence in their environment. Al-Jabin pointed a clear finger of blame at Arab governments, along with the Israeli government and the Jewish Agency, which were primarily responsible for the project of displacing Jews and gathering them in what later became known as the State of Israel.

Al-Jabin was not the first to humanize the Jews and simplify the approach to them as a beginning to understanding them and then restoring equal footing with them or those who hide behind them. He was preceded in this by Nasser Al-Din Al-Nashashibi in works like A Handful of Sand and Orange Seeds, which were deliberately forgotten. In Egypt, the Nasserist government worked hard to erase the Jewish heritage that could have passed through time, such as through cinema or song. Names like Togo Mizrahi and Leila Murad, along with her brother Mounir Murad, who both converted to Islam, were hidden.

What Al-Jabin did was shocking in a country like Syria. Through his captivating narrative, he presented the daily life of Syrian Jews, especially in the Jewish Quarter of Damascus, describing their community and its unique relationships with the surrounding social fabric. The novel was a qualitative leap for the author, who examined the Arab-Israeli conflict from different angles, aiming to understand Arab citizens who follow the Jewish faith and to deconstruct the intellectual and mythological ambiguities surrounding them. This ambiguity has always placed them in a complex position where they neither fully integrate with their citizenship nor completely detach from it. This existential crisis has consistently formed the core of the Jewish dilemma in all countries, providing the ideological foundation through which the Zionist movement entered the consciousness of world Jewry, convincing them of their distinctiveness, which eventually led to the establishment of a Jewish state. The idea of “us” and “them” is central, shaping the characters who feel that, though they are “here,” they belong “there.” The path of this movement is determined by awareness—or delusion—the illusion of belonging and difference, which pushes people to extremes in expressing their visions and perceptions, treating them as real life and existing reality.

After the success of Diaries of a Jew in Damascus, dominated by the character of Rahel, Al-Jabin published his second novel The Eye of the East years later, which also caused a stir, but from a different angle. Among the characters the author introduced, he reexamined and reconstructed the figure of Eli Cohen, the infamous Israeli spy who was executed in Damascus in 1965. Al-Jabin presented Cohen in a different light, portraying him not just as a spy but as a hunter of Nazi officers who fled justice and hid around the world, including in Damascus. Al-Jabin’s novel amazed readers, historians, politicians, and media alike with its bold interpretations and complex narrative.

In The Eye of the East, Al-Jabin also explored the relationship between fleeing Nazi officers hiding in Damascus and Cohen, who, according to the author, was not simply an Israeli spy but a pursuer of justice, tracking down these criminals to bring them to trial. This thrilling narrative further developed Al-Jabin’s distinct style, not just in literary imagination, but in his exploration of the world and its complex history.

In 2019, the same publishing house that released Al-Jabin’s works published the latest novel by the distinguished Syrian novelist and poet Salim Barakat, What About the Jewish Lady Rahel?, which addresses his long-standing interest in the intricacies of his beloved city of Qamishli and the relationships between its minority communities, including Arabs, Jews, Armenians, and Kurds. The novel revolves around the infatuation of a teenage boy with a girl from the Jewish quarter, with many other threads about the Kurds, Armenians, and the atmosphere of the 1967 war, as well as the cinematic fantasies of the adolescent youth.

Readers of both novels will find significant intersections between the two texts: Al-Jabin’s novel from 2007 and Barakat’s from 2019, published by the same house. These intersections go beyond the name of the central character, extending to the overall atmosphere of the novels and their foundational themes: the Jewish dilemma, the feeling of insecurity, displacement, and the role of society in pushing its members to leave, along with incomplete or lost love. Ultimately, both works reflect a kind of human solidarity with the Jewish character, even as society struggles with this solidarity.

Perhaps this is an unconscious inspiration between the two writers. After all, Al-Jabin continued his project of dissecting the Jewish character in The Eye of the East, offering a strange interpretation of Eli Cohen. In contrast, Salim Barakat reintroduced the same character in his latest novel. It is up to those who scrutinize the paths of floating ideas to discern how these thoughts intersect within Arab and world literature. What is certain is that Salim Barakat is a distinguished novelist and poet, who has carved a unique path in Syrian, Kurdish, and Arab literature, one that no one can ignore or erase.

This comparative reading of the three texts should be done with a critical eye to reveal the threads that connect them, and this responsibility lies with the publisher or editor. Perhaps what we are witnessing is an open history, a shared narrative in a complex nation. However, the expert writer always knows how to trace the originality of their own work and the ideas that emerged from their pages, even if they cannot do much about it. It is clear that Al-Jabin has both originality and a pioneering spirit. We leave the judgment to the experts, as these three texts stand together on the stage of Syrian and Arab literature. All we can do is read, enjo y, and appreciate.